The former European 400m champion explains why he chose to be so honest in his autobiography and how he hopes his story will help others

Iwan Thomas was never one to take the easy option. In fact, he used to go out of his way to make life difficult for himself. An example? Rather than park directly outside the Southampton track at which he trained, the former European 400m champion would instead drive up to the nearby ski centre.

Why? Because that way he would have to walk further and also come down a staircase of 76 steps to get to the track. More importantly, though, he would have to struggle his way back up those steps after his session, usually throwing up somewhere along the way.

In his mind, this was another way to push himself that bit harder, another way to make his already aching legs burn even more intensely, another thing that his rivals – particularly his British team-mate Mark Richardson – would not be doing.

“I used to get asked: ‘Why did you park there?’” Thomas recalls. “I used to lie and just say it was more private up there but, the truth is, I knew Mark Richardson would finish his session at Windsor and then get to his car or go back to the nice indoor warm-up track, get a massage then go home.

“I knew when I’d finished [training] I’d be sick. 40 minutes later, I’d finally be able to get my kit back on and then have to walk 76 steps back up to my car. My legs would be screaming but I knew that, maybe with the exception of [1992 Olympic 4x400m bronze medallist] David Grindley, no one trained as hard as me.

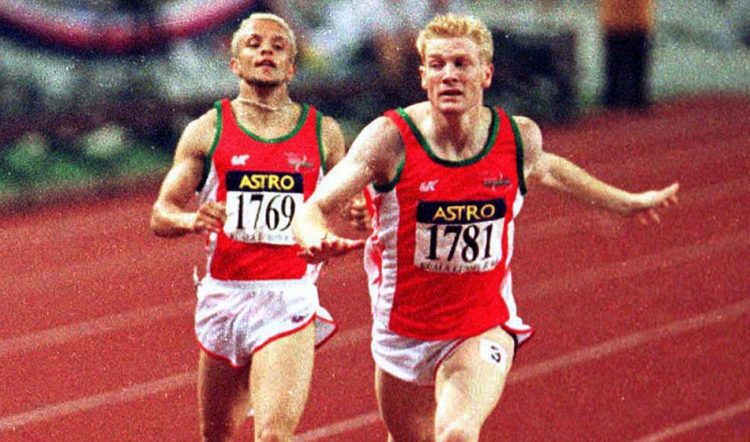

Iwan Thomas (Mark Shearman)

“Maybe it was stupid parking at the ski slope but it gave me that little mental edge. When I’d line up and I’d look across to my rivals I’d think: ‘Yeah, you want it, but you don’t want it as much as me because you’re not an idiot who parked at the top of a ski slope. That was just [one of the] things I did to help myself.”

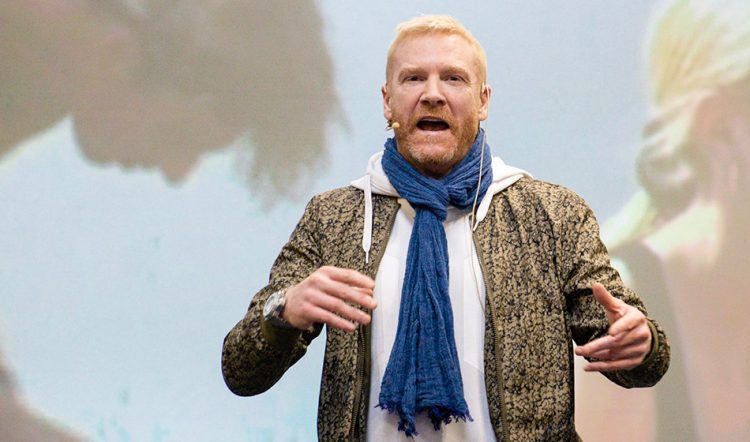

Thomas now admits that this philosophy of all-out attack, all of the time perhaps did the exact opposite in the long run. He is in reflective mood as he chats with AW, the purpose of the video call to talk about his new autobiography, Brutal. It is a searingly honest account of someone who took on everything, everywhere all at once – whether that be with the aim of winning his father’s approval, earning a compliment from his demanding coach Mike Smith or challenging for the greatest titles in a sport he has been able to fall back in love with but, for a while, also grew to loathe.

The tale of the 76 steps says a lot about Thomas, British 400m record-holder for 25 years, European and Commonwealth champion in 1998, as well as a world champion and Olympic silver medallist in the 4x400m relay. When things were good for the 50-year-old, they were very, very good. But when they were bad, they were horrid.

His body struggled to cope with the demands he would continuously place upon it and, eventually, it succumbed. Typically, there were numerous occasions when Thomas fought to claw his way back from injury for one last hurrah but his fairytale wish of bowing out to great fanfare never materialised. Instead, he had to come to terms with fading into the background.

Iwan Thomas (Mark Shearman)

“I think [going full pelt at everything] was probably my downfall as well,” he says. “Even as a young boy, when I did BMX racing, it was all or nothing. I don’t know if it’s an addictive personality, but I used to get something out of being the best – or putting myself up against the best and giving them a bloody good race.

“Whether it was on the school playing fields, kicking a football, with a rugby ball in my hand, whatever it was, there was something in my mind, that do or die mentality that I had to win at everything. I still have that. It’s turned down a bit now but I always gave everything.”

It’s an attitude he has also taken into his second career, as a broadcaster, TV personality, in-field stadium presenter and now author.

“For some parts of the book, putting pen to paper was really quite therapeutic and it’s nice to reflect sometimes,” says Thomas. “But then there are other chapters, where things got a bit darker for me and it was quite hard.

“It took me a long time to accept I was no longer Iwan Thomas the athlete and it was a long, long time for me to come to terms with the fact my body had let me down and my career didn’t end in the lovely way I would have liked it to have done.”

Iwan Thomas

That was, he admits, the darkest time – but there had been a build-up. Depression crept over him. Every injury was a stern test of his physical and mental powers of recovery, but he was programmed never to ask for help.

“Because I had come from a tough event, I was six foot two, I never showed weakness,” he continues. “That was my strength on the start line. I’d eyeball my opponents and I’d want them to be scared of me.

“So I felt that, when I was going through a dark time when I was injured, I couldn’t reach out and say: ‘Hey, listen everyone, I’m really struggling here mentally. I don’t know if I’m going to get back. I don’t know what I’m going to do with my life’.

“I felt: ‘If I show any weakness then, if I do get back to the track, they’ll know I’ve got a chink in my armour, and I’m not going to allow that to happen’. By me being pig-headed and a stubborn bloke thinking ‘I’m alright’ and not talking to anyone, I kind of bottled it up and made it worse for myself. I’ve been honest in the book, showing there’s a side to sport which isn’t great – it is tough, it is lonely and it is soul destroying.”

Thomas’ hope is that his words will help other athletes who might be struggling, that they avoid the mistakes he made and are persuaded to open up and talk to someone.

But to say that he views athletics entirely through the prism of a resentful former pro would be entirely wrong. This is not some sermon denouncing the evils of athletics, and the father of three will not hesitate to get his young boys involved when the time is right.

Laura Muir and Iwan Thomas (Mark Shearman)

“It’s an amazing sport and I also think it teaches you a lot of life lessons that you can then take into the real world,” he says. “When they’re old enough I one will 100 per cent be encouraging my boys to do athletics. I’m not sitting here as a grumpy, old, retired man thinking the sport was horrible to me, because it wasn’t. I’ve got a very fortunate lifestyle because sport gave me something and I’ll always be grateful for that opportunity.”

The pitch of Thomas’ voice changes and the enthusiasm levels click up a little as we get to the nitty gritty of his old event. The lull that hit British men’s 400m running after his retirement, as well as that of Roger Black, Jamie Baulch and Richardson, is being replaced by a new sense of hope. Matthew Hudson-Smith is now not only the British record-holder, but the fastest European in history. Charlie Dobson, to whom Thomas has been a regular adviser, is also beginning to deliver on his clear potential.

They are competitors, to use the book title, in an event that is “brutal” but the black and white nature of it is part of the appeal.

“Maybe I’m slightly sadistic, but I loved the 400m,” says Thomas. “I wasn’t good enough to do the 200m, I never tried an 800m but for the 400m I really used to embrace the pain of training.

“Maybe that was my weird way of self-harming or pushing my body to the limit, but I think in any event the better you are, the margins are so fine between winning and losing. The stopwatch doesn’t lie, does it? You either run fast or you don’t. You either jump high or jump far or throw far or you don’t.

“I think you need a combination of things to be a good 400m runner. You need the speed, you need the speed endurance, you definitely need strength and you need something there, as well,” he adds, tapping the side of his head and grinning. “Actually, you need something missing there.

“You’ve got to be a bit crazy to do the 400m. You’ve got to like pain. In the starting blocks, I never used to think: ‘Oh, this is a whole lap of the track. The last 30 metres might hurt’. I would think things like: ‘I’m going get on his shoulder by 50m, I’m going to get past him by the 200m mark. I would attack the race and, yeah, it’s gonna hurt for a bit at the end, and then I’m going to be sick, but then I’ll go home and I’ll feel great.”

In the here and now, Thomas is feeling pretty good, too, with a busy work schedule in front of him that includes the Paris Olympics. From his current vantage point, then, what words of advice would he have for his younger self?

“Listen to your body. Don’t be afraid to stand up to your coach and if you know something’s not right, it probably isn’t,” he says. “There were a number of times I had a slight niggle or something was a bit tight and I thought I could carry on and then I’d tear my hamstring and I’d be out for weeks.

“I’d also tell myself that it’s going to be all right. Life is going to be all right and that’s way beyond athletics.

“I would say enjoy your youth, too, because you’re not going to be young forever. You think you’re going to have a six pack forever and that you’re going to be the fastest, the fittest there is. You’re not. Before you know it, you’re going to be 50 years old training in a gym most nights trying to keep up with youngsters and reminiscing about how you used to be someone.”

A self-deprecating laugh follows that last comment, as well as the perfect note upon which to finish.

“You’ve just got to enjoy it as well. In any event, you really have to realise you’re part of a wonderful sport. Make hay while the sun shines. Listen to your body but when you are fit, just enjoy it. If you’re somebody that likes racing, go out and race. If you like training and you don’t want to race as much, do that. Just find your happy place.”

It took time to get there, but that is exactly what Thomas has done.

Iwan Thomas’s book Brutal is out now.

» This feature first appeared in the July issue of AW magazine. Subscribe here

The post Iwan Thomas’ new book pulls no punches appeared first on AW.